Working as a group has some very distinct advantages. Collectively, you possess a greater, broader set of skills and resources, and the underlying peer pressure keeps you on track and braver than you would be as an individual. While these are all great perks to working together, the greatest advantage of all is the development of an idea. Sitting around a table with beers and notepads, PDL met regularly to discuss the kinds of projects we wanted to explore, and how they could be improved, or come to life at all.

Offspring at the Olympic Sculpture Park was a playful way to interact with large-scale sculpture at the newly-christened OSP, giving the existing works new identity and humanity. Many of these large-scale sculptures were large and abstract, cold and inaccessible. Giving them offspring allowed the viewer approach them in a new light, one with more humor and personality.

We first started with Roxy Paine’s Split — a sixty-foot tree constructed of polished stainless steel and anchored in an open prairie. On opening day, we slipped into the crowd holding a little thee-foot tall stainless steel sapling. Security guards were on high alert and the prairie was fenced off and inaccessible. Do we turn away? Make a break for it like a fan running across a baseball field? In the end, we found a patch of lawn close to Split and spiked our little offspring in the grass. We called it Splinter, and we left a small nameplate attributing the work to darlings-of-the-Seattle-art-world SuttonBeresCuller. About an hour later, the museum’s executive director was summoned over by security to evaluate the intruder. She loved it. Especially that SuttonBeresCuller had deigned to grace them with a savvy prank. And Splinter stayed in the park for the next three days. SBC got several confusing personal calls of congratulations for that one.

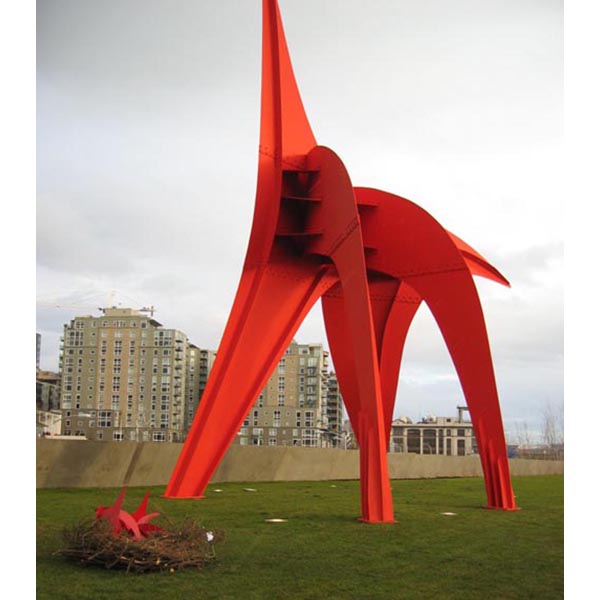

We had a long list of sculptures that could be mothers. And with a slight nod from the museum staff, it was time to do some baby-making. It was, after all, spring. The second time around we set our sights on Alexander Calder’s Eagle — the crown jewel of the park — a thirty-five foot red-painted steel sculpture that stood in the center of the park overlooking Elliott Bay. We built a large nest out of branches, and Jason crafter three miniature versions of the Calder out of PVC foamboard, which we entitled Eaglets. And on a beautiful Saturday morning, we boldly walked the four-foot diameter nest into the park and set it on the grass beside the Eagle. It looked great, and park-goers (especially kids) got a kick out of it, but would it last? The following weekend the museum staff included it in their park tour. A few weeks after that a strong wind blew an eaglet of the nest and the park took the set into custody. We are confident that they are being well cared for. Incidentally, this piece got the most national press for anything we've done to date- featured in media from ARTnews magazine to Minnesota Public Radio, speaking to the appeal that humorous dialogue with public sculpture has in the oft-too-serious world of fine art.